If you are an employee and have your retirement savings tied up in one of the public pension funds, you should stay active and be abreast of how your fund is performing. A percentage of your income is taken each pay day and put into an investment fund that will purportedly provide you income when you can no longer work or retire. Seems basic enough, right? Well, it actually isn’t that easy. Pension funds across the country must each year estimate how much they expect to earn on investments—a projection that determines the amount the government that is affiliated with the pension fund must pay into it. The greater the anticipated returns, the less need for government support.

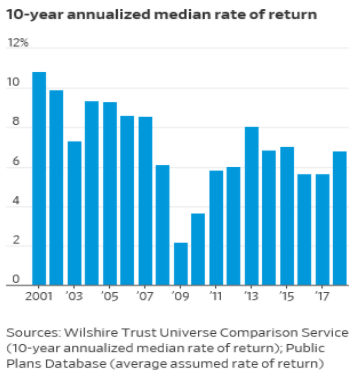

According to Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service, yearly returns on public pension plans have returned a median 6.79 percent over the past decade and 6.49 percent over the past 20 years. When big money is involved, you can be sure politicians are right behind it. Obviously, it is political capital when funds raise their target rates, because the governing body will have to take less of your current income to pay for your future retirement. But the problem is that public pension plans have what some would say is way too much control over how they predict their returns. Always remember that one of the basic tenants of finance is risk versus reward. The more risk you take, the more you should be rewarded for it, and vice versa.

Some entities, like California and its school districts will have to pay a projected $15 billion or more into the state’s public worker pension plan over the next 20 years after the plan, known as Calpers, in 2016 decided to reduce its investment target to 7 percent from 7.5 percent over a three-year period. On the flip side, you have Birmingham, Alabama, which raised its target rate on one of its pension funds to 7.5 percent from 7 percent in 2016 after moving some of the money out of fixed-income investments and into equities. Anecdotally, the timing of shifting funds from bonds to stocks is not good. As with the general public, these private pension plans tend to step into the market and buy at peaks. Richard Ciccarone, president and chief executive of Merritt Research Services LLC, a research firm, states, “Why Birmingham changed the investment rate return…is a bit questionable.” South Carolina is another example. Years of ill-timed investments and a refusal to abandon questionable strategies have left South Carolina’s government pension plans on the ropes, with a massive funding gap that threatens promised benefits to future retirees. State Treasurer at the time, Curtis Loftis, explains, “We have lost so much money the state will be lucky to get out of it.” Not a good scenario for teachers, firefighters and one in nine residents of the state.

A delicate balance needs to take place in the world of public pension funds. On one side you have the portion of employee income taken and invested. What that gets invested in is in large part determined by the rate of return estimated by the pension fund. Tom Aaron, senior analyst, Moody’s Investors Service, agrees by saying, “You’re supplanting a budgetary contribution with increased risk taking. If those (investment) assumptions don’t pan out that’s going to result in higher than expected budgetary contributions down the road.” Hopefully the right amount will be paid today, so that public pensioners can retire in peace tomorrow.