When the Oracle of Omaha speaks, people listen.

The letter to shareholders in the annual report of Berkshire Hathaway is legendary in the financial community, and the most recent version was released Saturday. People are generally interested in what one of the wealthiest old men in the world has to say.

Buffett, 92, and his long-time partner Charlie Munger, 99, have compiled one of the best investment records ever. One thing that struck me was that Buffett himself stated that he has been around and investing for almost one-third of the time this nation has existed. Unbelievable. So when it comes to understanding finance and how to value companies, will you listen to Warren Buffett or Elizabeth Warren?

Despite his support of Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden, when it comes to finance and economics, he is only partial to the dollar.

Buffett blasted opponents of stock buybacks in his annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway Inc. shareholders, writing that the opponents are “illiterate” about economics or are engaged in demagoguery. Harsh words indirectly aimed at Bernie Sanders and the other Warren.

Besides those just mentioned and MBA types, you’d be hard-pressed to find a friend who can’t sleep at night worrying about corporate buybacks. What are they anyway, and why all the fuss?

Simply put, a corporate stock buyback is when a company uses its cash to buy back some of its own shares from the market. This reduces the number of shares outstanding and increases the ownership stake of the remaining shareholders.

A company may do this to return money to shareholders or to boost its stock value. The illustration below, courtesy of the Motley Fool, exhibits this.

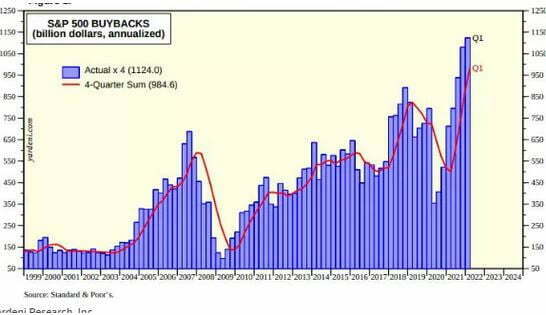

Over the past few decades, stock buybacks have become a big part of how companies use their profits to return capital to shareholders. According to data from the Motley Fool, in the first quarter of 2022 alone, companies announced more than $300 billion in new repurchase authorizations, an all-time high.

In 2021, repurchases totaled $880 billion just from companies on the S&P 500 index, and it’s estimated the total will exceed $1 trillion in 2023. Starting in 2023, public company stock buybacks will be subject to a 1% excise tax, purportedly decreasing their attractiveness to businesses. You wonder why liberals salivate at the mouth thinking about taxing that $1 trillion amount and the enormous amount of good it can do in creating a transgender bathroom sign for any restrooms in need.

In all fairness, there are two sides to the coin of stock buybacks. But which is it?

As it turns out, stock buybacks have advantages and disadvantages for stock issuers and investors. To begin, the only reason that a corporation can buy back its stock is that it has generated extra cash. For corporations with extra money, there are essentially four choices to make:

- The firm can make capital expenditures or invest in other ways in their business.

- They can pay cash dividends to the shareholders.

- They can acquire another company or business unit.

- They can use the money to repurchase their shares—a stock buyback.

Like a dividend, a stock buyback is a way to return capital to shareholders. A dividend is effectively a cash bonus amounting to a percentage of a shareholder’s total stock value.

However, a stock buyback requires the shareholder to surrender stock to the company to receive cash. Those shares are pulled out of circulation and taken off the market until they are reissued or dissolved.

Among the biggest share repurchase announcements have been Chevron Corp.’s $75 billion buyback program, the $40 billion plan of Facebook META, and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s $30 billion authorization. Stock buybacks of this magnitude can often bode well for the market in general. According to Ben Silverman, director of research at the investment-research firm VerityData, “Buybacks continue to be robust and provide a buoy for individual stocks and the market broadly.”

So what’s the downside?

Even as the U.S. continues to experience its longest economic expansion since World War II, the concern is growing that soaring corporate debt will make the economy susceptible to a contraction that could get out of control. Macro economically, one of the main culprits is allocating cash via debt to finance share repurchases.

According to JPMorgan Chase, the proportion of buybacks funded by corporate bonds reached as high as 30% in both 2016 and 2017. At the corporate level, the all-important EPS metric can be influenced. EPS divides a company’s total earnings by the number of outstanding shares; a higher number indicates a stronger financial position.

By repurchasing its stock, a company decreases the number of outstanding shares. A stock buyback thus enables a company to increase this metric without actually increasing its earnings or doing anything to support the idea that it is becoming financially stronger. This is where critics will say that corporate executives with options or other pay metrics tied to EPS will potentially abuse the system for their own gain.

The Harvard Business Review goes further by saying that stock buybacks made as open-market repurchases do not contribute to the productive capabilities of the firm. Indeed, these distributions to shareholders, which generally come on top of dividends, disrupt the growth dynamic that links the productivity and pay of the labor force.

The results are increased income inequity, employment instability, and anemic productivity. That sounds like Harvard.