September is right around the corner, and it is often a precarious time for the stock market. There is something known as the September effect, which refers to the historically weak stock market returns observed during the month of September.

In fact, September has been the worst performing month, on average, going back nearly a century. This theory flies in the face of the efficient market hypotheses (EMH), which states that stock prices reflect all available information and gaining any consistent alpha, or return over market, is impossible.

As you may have guessed, the September effect is a supposed market anomaly whereby stock market returns are relatively weak during the month of September. It’s considered an anomaly because it violates the aforementioned efficient market hypothesis.

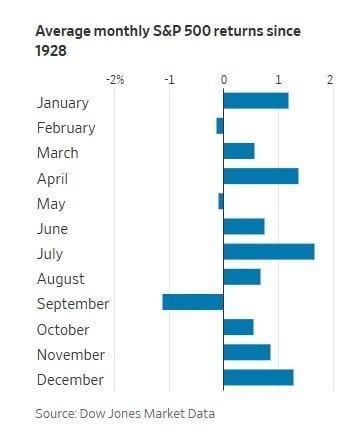

Anomalies aside, statistics don’t lie, albeit for reasons unknown, that September is in fact a down month for the markets. The S&P 500 has lost an average of 1.1% in September dating back to 1928, making it the worst month for stocks’ performance.

So whether it’s an anomaly or seasonal pattern, there is cause to attempt to understand why this effect takes place. There are several theories behind the September effect that we can take a look at. Can we blame it on the doldrums of summer? If you look at what Wall Street refers to as the “fear gage,” the Cboe Volatility Index, you’ll find its calm and sitting well below its historical averages. Summer can be uneventful unless triggered by news or other non-systemic events.

According to Sam Stovall, chief investment strategist at CFRA Research, “Investors get back into the markets full swing in September following a summertime lull, and their refreshed analyses likely cause them to make adjustments to their portfolios.”

Stock prices are driven by supply and demand. When the market declines in general, simply put, more people are selling than buying.

Or should we say more institutions?

Many mutual funds have fiscal years ending in the fall, provoking them to sell their losing stocks for “window-dressing” purposes. They use September to dump losing positions so as not to look bad when reporting holdings to shareholders. So far in August, the S&P 500 is down 1.9%, compared with its average gain of 0.67% for the month. The information technology sector, this year’s best performer, is down about 3%.

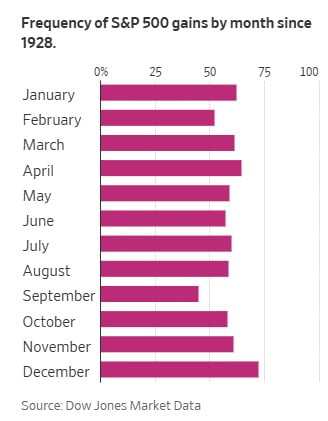

August is about an average month in frequency of gains.

Another factor that is tossed around is the wealth effect of paying tuition in the fall. With this hypothesis, many investors must sell large amounts of their stock holdings to pay their children’s tuition bills at colleges, universities, and prep schools. And for most, the school year begins roughly in September. That one seems a bit of a stretch, but who knows.

For you psychologists out there, you’re familiar with what is known as Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). I wonder which came first, the acronym or the name itself. One would image that a college could get a grant for anything if this could be researched.

A university study suggested that the sharp drop in the amount of daylight in New York City in September might trigger Seasonal Affective Disorder, a type of depression related to changes in seasons. As a result, according to this hypothesis, some investors become more risk-averse, so they sell losing stocks, unwilling to wait for things to get better.

The unprecedented rate hikes by the Fed will also play into the September effect this year. As rates rise, yields on bonds become more attractive as compared with equities. The 10-year Treasury yield is at its highest level in over a year, leading some to think this might cause stocks to retreat in September.

This also assumes that the Fed is done with raising rates. Many investors think the Federal Reserve will need to keep rates higher for longer, particularly with rising oil prices threatening to stoke inflation again.

According to Rob Williams, chief investment strategist for Sage Advisory Services, “We’ve just been through the most aggressive hiking cycle in my career. It’s a bit presumptuous to think we’ve felt all those effects.”

So where does all this leave investors? It’s hard to say, but perhaps the best move is no move at all. Remember, there is a difference between market timing and seasonality. Seasonal trends reflect how the market will behave in particular months as part of a long-term trend.

Market timing is based on short term price patterns. Timing the market perfectly is, of course, impossible. As discussed above, seasonal trends are grounded in the analysis of years of data, but not every year is identical.

There is also an October effect, but that’s a story for another time.