The dichotomy that exists between the European north and south is an economical grand cannon. From the origins of the euro and throughout the last decade the dispersion has grown to such an extent that economists and politicians wonder if the Eurozone can survive.

At the crux of the issue is inflation and the need for the European Central Bank (ECB) to raise interest in an attempt to fight such inflation. Countries like Germany and France in the north are proponents of such measures, urging the ECB to follow a rate hike policy similar to the Fed in the U.S. However, countries like Italy, Greece, and Spain in the south see this move as deleterious to their economic health and possible sovereignty.

Europe’s deteriorating financial position has caused the ECB to raise interest rates for the first time in more than 11 years. The ECB said it would raise its key interest rates by 0.25% in July, with further increases planned for later in the year. The bank also intends to end its bond buying stimulus program on July 1.

What you’re currently seeing in Europe is basically a mirror image of what’s going on in the U.S. The latest Eurozone inflation estimate was 8.1%, well above the ECB’s target of 2%. Seema Shah, the chief strategist at Principal Global Investors, noted, “With this inflation outlook and the unavoidable path for higher rates, the ECB is facing stagflation threats full-frontal.”

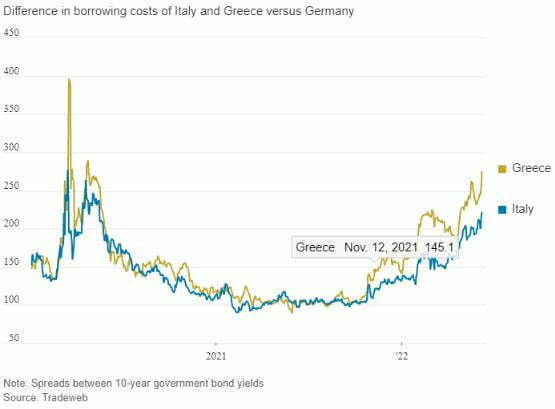

As mentioned, countries in the south of Europe will experience rising borrowing costs associated with any ECB rate hike policy. Traders are quick to understand this, and are beginning to dump southern European government debt. The chart below depicts the spread in borrowing costs between Italy and Greece versus Germany.

From the outset of the monetary union of Europe in the 90s, the notion of a financial crisis was ever present. The convergence of interest rates across the countries meant much lower rates for places like Portugal, Greece, and Italy. The alluring rates allowed for abundant credit in these countries, and if utilized correctly could translate into healthy economic growth.

This was not the case in the early 2000s. The current account deficits increased for austerity and other progressive policies, increasing a country’s external debt until external credit stops being granted. Traders are sensing this is where southern Europe is today. While they were accumulating large stocks of external debt, some of these countries were also amassing very significant amounts of public debt.

The current question that the ECB must ask is whom they favor in their economic focus. Just like the Fed, the ECB is mandated to fight inflation and maintain price stability of the euro. However, the effects from such tools impact multiple variables which have important macroeconomic consequences for Eurozone countries, such as FX rates or credit spreads.

This, coupled with an asymmetric impact on the moves of these variables for different countries creates a huge dilemma for the policy makers behind ECB’s decisions. According to James Athey, an investment manager at Abrdn, “Italy is a much weaker economy and weaker credit than Germany. For the last decade, these economies have been diverging, the imbalances between them get bigger and bigger. The only reason the spread has been so low is because the ECB has been forcing it there.

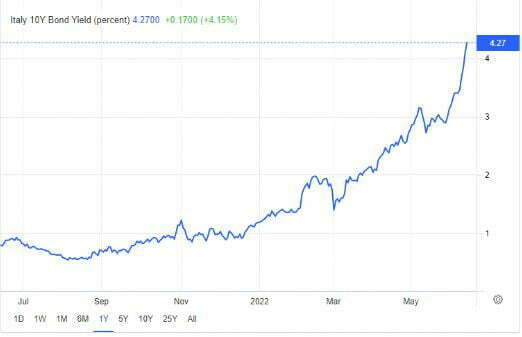

Now this is changing.” The ECB walks an exceptionally tight line in that they have all of the responsibilities and duties of the Fed, with the addition of maintaining a balance between the haves and have-not countries. ECB President Christine Lagarde tried to reassure investors recently that the ECB would support southern European governments, including by creating new bond-buying tools if necessary. However, few details were offered to make for a volatile market in these bonds. As shown below, yields have surpassed 4% in the Italian 10-year bond.

It’s not a simple question with a simple solution. Inflation fooled the best and brightest minds in the U.S. without having the caveat of sovereign debt default. Europe is experiencing broad record inflation, way above the defined target for price stability, meanwhile, credit spreads are already very high compared to historical values, mainly for peripheral countries, and the Euro FX is at some of its lowest levels, especially against the dollar.

Should the central bank tighten financial conditions to fight inflation and strengthen the Euro but, at the same time, risking a default crisis in peripheral countries? My guess would be that Lagarde and her cronies in Brussels would likely throw the south under the bus before giving in to inflation.

Perhaps these new bond buying tools will gain approval and postpone what is probably the inevitable. Lorenzo Codogno, former director general of the Italian Treasury Department, puts it this way, “Lagarde is pretending the ECB is ready to act forcefully, and that firepower is close to infinity, a sort of ‘whatever it takes’.”

The new world order and one world currency sounded pretty good to the Eurozone in the 90s. It’s taken 30 years for it to unravel and probably a bit longer until its death knell.