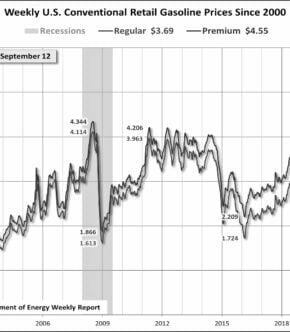

If you thought that the only pain you’d be feeling from higher gas prices was at the pump you would be mistaken.

Arguably for the last year the greatest cost to consumers has been rising gas prices, but according to experts and commodity companies, the pain is trickling down from the pump to the kitchen. The link between soaring natural gas prices and the food table is one of concern for not just the U.S., but the world in general.

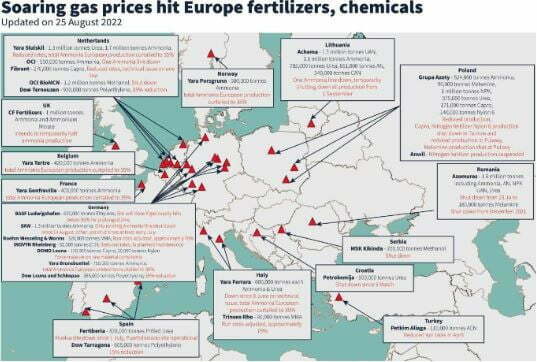

Rising natural gas prices across Europe, a key producer of chemical fertilizers, will weigh on food production and security, according to Norway-based Yara. The chemical company has seen a nearly fifteen-fold increase in natural gas prices, which has forced it to reduce its production of ammonia, a major component of fertilizer. As prices for fertilizers rise in the wake of those for natural gas, farmers will be tempted and perhaps forced to cut back on their use. As a consequence, the production of food crops could drop.

Europe is getting hit particularly hard. European chemical companies that use natural gas as a source of energy or raw material are reeling from another price spike in the region. In the past several weeks, the price of gas hit a record $342 per megawatt-hour, double that of a month ago and several times as much as the price a year ago. So what do chemical companies do that use high-priced gas to make ammonia? They shut down.

The fertilizer company CF Industries says high prices for natural gas have forced it to temporarily halt production at its ammonia plant in Billingham, England, which provides about one-third of the UK’s commercial-grade carbon dioxide. In case you needed another reason to be pissed off at Putin, Russian gas would be it. Recent surges in gas prices are linked to a decision by the Russian gas supplier Gazprom to temporarily close the Nord Stream pipeline, which moves gas from Russia to Germany. As the following map dictates, high gas prices are being felt and reflected in costs all across Europe.

The cut in production by European companies, including Germany’s BASF, have a direct impact on agriculture in the U.S. According to Kevin McNew, chief economist at Farmers Business Network, “Most of the ammonia used to make the nitrogen-based fertilizers that are essential to modern farming comes from natural gas. So when ammonia producers like BASF cut back on natural gas, that can impact the supply of fertilizer needed to grow a variety of crops.”

So how does this translate into dollars and cents? Farmers in the U.S. spent roughly $28 billion on fertilizer last year. Analysts predict that number will be well north of $40 billion this year. As such, consumers can expect food prices to continue to climb as well.

According to the World Bank, fertilizer prices have risen nearly 30% this year, following an 80% increase in 2021. Soaring prices are driven by a confluence of factors, including surging input costs, supply disruptions caused by sanctions (Belarus and Russia), and export restrictions (China). Concerns around fertilizer affordability and availability have been amplified by the war in Ukraine.

While natural gas gets the headlines, coal is also a culprit in rising input costs. Soaring prices of coal in China, the main feedstock for ammonia production there, forced fertilizer factories to cut production, which contributed to the increase in urea prices. Higher prices of ammonia and sulfur have also driven up phosphate fertilizer prices.

Prices have risen in response to the war in Ukraine as well, reflecting the impact of economic sanctions against Russia as well as disruptions in shipping lanes in the Black Sea. World Bank statistics state that Russia accounts for nearly 16% of global urea exports, with urea prices surpassing their 2008 peaks. China has taken steps to protect itself in the event of shortages. It has suspended exporting fertilizers temporarily to ensure domestic availability.

On the demand side, consumption remains strong with the U.S. and Brazil allocating record acreage to grow soybeans, which are a fertilizer-intensive crop. The pressure on both the supply and demand side have pushed fertilizer prices to levels not seen since the 2008 global food crisis.

While natural gas prices are off of their August highs, fertilizer prices will remain high until we see a pullback in gas prices. As such, expect the inflationary pressure to continue to push food and chemical prices higher as well.