In his annual address to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, CEO Warren Buffett and his right-hand man, Charlie Munger, noted that they were not worried about the government defaulting on its debts. They alluded that since 1960 Congress has raised the debt ceiling 78 times and will certainly do it a 79th.

Similarly, the oracles from Omaha also warned that although a banking crisis is possible, the fact that the FDIC covers demand deposits to $250,000 has in the past and should, in the future, give depositors comfort that their savings are safe.

Even if a debt ceiling agreement is reached by June 1, raising such a ceiling by trillions of dollars is not good. As we are currently aware, negotiations are taking place this week between President Biden and Speaker of the House, Kevin McCarthy in an attempt to keep the doors of the federal government open.

If the debt ceiling is not a wall on top of the Lincoln Room at the White House, just exactly what is it, and what does it mean?

Historically speaking, the debt ceiling is the maximum amount of money that the United States can borrow cumulatively by issuing bonds. The debt ceiling was created under the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917 and is also known as the debt limit or statutory debt limit. Alluding back to the Buffett shareholder meeting, time and time again, questions were asked about wealth and money and how to become financially secure. The answer was remarkably simple.

Don’t spend more money than you make; you can earn a nice living and have a nice life. Let’s extrapolate that message to the federal government. In the fiscal year ending 2022, the United States government spent $6.27 trillion more than it collected, creating a deficit. Like the retained earnings of a corporation, the national debt represents the sum of past deficits. The current dollar limit on federal debt is $31.4 trillion.

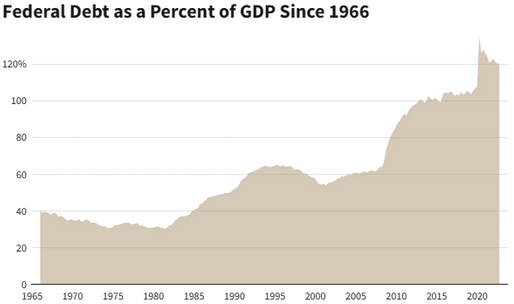

However, the national debt in dollars is generally viewed as less important than its proportion to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) or the debt-to-GDP ratio. That’s because a country’s tax base grows alongside its economy, increasing revenue that the government can raise to service the debt. At the end of 2022, the U.S. national debt-to-GDP was 120.21%.

With that said, what kind of congress and administration would actually consider increasing spending when they are currently trillions of dollars in debt?

The Biden administration of course. Even Biden’s own government employees have turned against him, albeit for financial and not political purposes, of course. The National Association of Government Employees (NAGE) filed a lawsuit to block enforcement of a law that sets the nation’s debt limit, arguing it is unconstitutional as a political divide over raising the borrowing cap comes to a head.

NAGE represents nearly 75,000 federal employees and asserts that its members are at imminent risk of layoff or furlough once the limit is reached. Even transitory inflation martyr Janet Yellen is on the right side of this one. In mid-January 2023, the Treasury Secretary reiterated the importance of Congress raising the debt ceiling to avoid a potential default.

Although highly unlikely, what would transpire if the U.S. defaulted on its debt? Shakiness in U.S. creditworthiness could result in some market turmoil, like in 2011 when the U.S. faced a debt ceiling crisis and received a downgrade in its credit rating.

According to Ross Mayfield, an investment strategy analyst at Baird Private Wealth Management, “That year, we saw a lot of market volatility. Stocks really sold off around this event, with companies linked to the government selling off even further.”

So what does this mean for you? Aside from stock market volatility, you’d see ramifications across the economy. Any ding in the U.S. credit rating would likely raise rates on other types of debt, such as mortgages and auto loans, to account for additional risk. Do you receive Social Security benefits? About 66 million retirees, disabled workers, and others receive monthly Social Security benefits.

The average payment for retired workers is $1,827 a month in 2023. These payments could be delayed as a result of a default on the debt. Federal employees and veterans are also on the front lines of a federal debt crisis and like Social Security recipients, are in danger of payments being delayed.

In the bigger macroeconomic picture, a debt default could trigger an economic downturn, which would prompt a spike in unemployment. It would come at a particularly fragile time when the nation is already dealing with rising interest rates and stubbornly high inflation.

According to Moody’s, if the default lasts for about a week, then close to 1 million jobs would be lost, including in the financial sector, which would be hard hit by the stock market declines. Also, the unemployment rate would jump to about 5% from 3.4%, and the economy would contract by nearly half a percent. A more draconian scenario shows that if the impasse dragged on for six weeks, then more than 7 million jobs would be lost, the unemployment rate would soar above 8%, and the economy would decline by more than 4%, with the effects being felt for more than a decade from now.

In reality, the debt ceiling will be amended to some degree, and life will likely go on with it being unnoticed by most. We’ve been there many times before and will likely, and unfortunately, be there many times again.

The current problem is political and is wagging the economical tail of the U.S. economy.