It’s been rather quiet in terms of small and regional banks since the downfall of First Republic Bank, Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. Perhaps this could be the quiet before the coming storm. Nothing has changed really, except maybe that larger economic issues like inflation and interest rates have pushed the interest in regional banks to the side. The only reason that they would be newsworthy again would be of course for deleterious events in the small bank marketplace. It’s not because the economic climate has gotten better for them. It’s actually gotten worse. Just ask Doak Harley, the chairman of Industry Bancshares, the parent of six banks in rural eastern Texas. He must answer unnerving questions from customers, such as why does the bank have a negative net worth, and what exactly does that mean going forward.

As evidenced by those mentioned above, decisions made by bankers during a period where money was flush and rates were low, are now coming under the crushing pressure of what has been rapid Fed rate increases. The math behind the negative net worth of Industry and others comes largely from their bond portfolios. Most acting under the assumption that long term rates would stay near zero for eternity, piled into 10 and 30 year bonds when rates were low. As the Fed began its draconian tightening, the value of the current bonds banks held plunged, with many now having more liabilities than assets on their balance sheets.

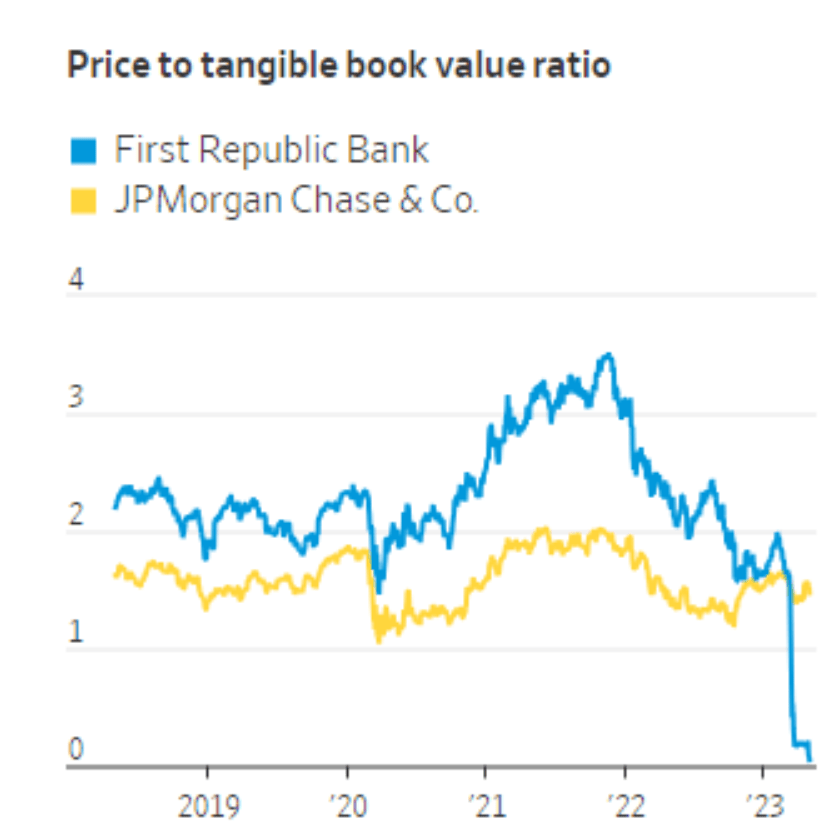

In hindsight now what was perhaps the pinnacle for First Republic and other regional banks was late in 2021, when actual book value ratios exceeded that of larger money center banks. The following compares price to tangible book value of First Republic and JP Morgan Chase.

The banking business model is good until it isn’t. Customer deposits fund loans to the community in small banks. When the Fed tightened and rates rose, these depositors took off for higher yielding returns at the big money center banks and online institutions. New federally insured accounts can be opened and transferred in minutes. CEO Mike Daniels of Nicolet Bankshares, a 60-branch bank in the Midwest, put it this way, “Our raw-material costs just went up 600%,” referring to his deposits, or lack thereof. Thousands of small and midsize banks across the U.S. flourished after the 2008 crisis. Despite an imposing regulatory environment, ultralow interest rates kept the deposits coming in. Borrowers enjoyed the local lenders who could get to know them and their needs, both personal and business.

There was, however, a window of opportunity to act. The Fed didn’t begin its rate hike until March of 2022, so there was ample time to segue out or hedge against their current bond portfolios. The thought process of small banks at the time was to increase interest paid to depositors, while simultaneously raising the rates they charged to borrowers. Makes sense. What they didn’t see coming were the rapid fire Fed hikes and the before mentioned trio of bank defaults. Main Street America got nervous and started pulling deposits out of smaller banks for fear they might meet the same fate as Silicon Valley bank.

Interest income is at the heart of the business model of community banks. They deal in plain vanilla loans. They take deposits in and lend them out for profit. Margins got tight and deposits dried up. In the first quarter, community banks paid on average 1.14% on deposits, up 0.39 percentage point from the prior quarter, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. They earned 5.36% on loans, up 0.16 percentage point from the prior quarter. Larger money center banks also use this model, but have more cushion because of a more diversified business. They can pay higher rates because of fee-based services like trading desks, wealth management and investment banking. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, Community banks’ profits are expected to decline 23% this year, which is larger than the 18% decline expected from the industry as a whole.

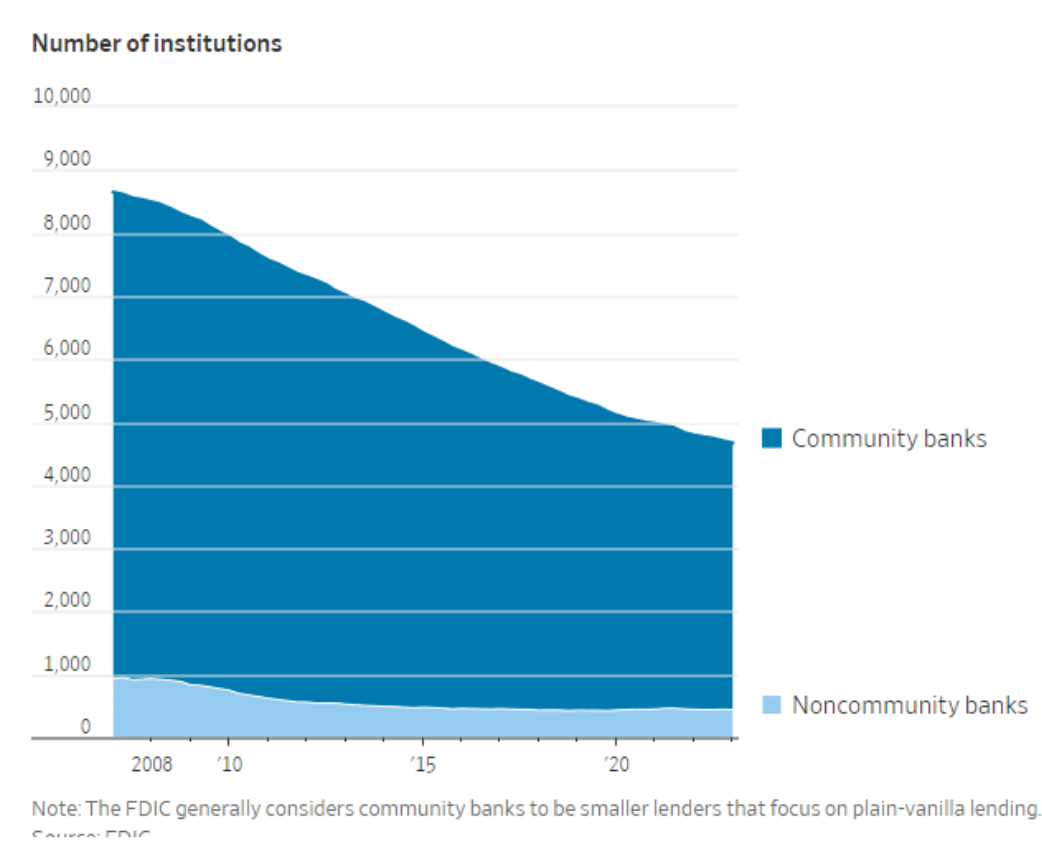

When things get tough in any industry consolidation occurs, and banking is no different. According to the FDIC, the number of banks in the U.S. today is roughly 4,700, down from 8,000 a decade ago.

For those small banks that remain, competition for funds will be fierce. It’s not just individuals and the private sector chasing yield, but also less astute types such as municipalities and school districts. When it’s as easy to do, everyone is doing it. According to Chip Reeves, CEO of MidWestOne Financial Group, “It’s probably the greatest deposit competition that I’ve seen in my banking career.”

One often wonders about unsecured deposits at these and other institutions. In the first quarter, community banks lost about $60 billion in deposits that were over the deposit insurance limit, the FDIC said. This number is likely to continue to rise. Depositors who were once somewhat comfortable with the safety of these unsecured deposits are now changing their tune. Again, the simplicity of making a change to a larger financial institution or brokerage firm where one can invest in a host of security options backed by Treasurys yielding 5% has become a no-brainer. Even with the Fed pivoting likely to begin in early 2024, these deposits and others aren’t likely to find their way back to the local small bank again.