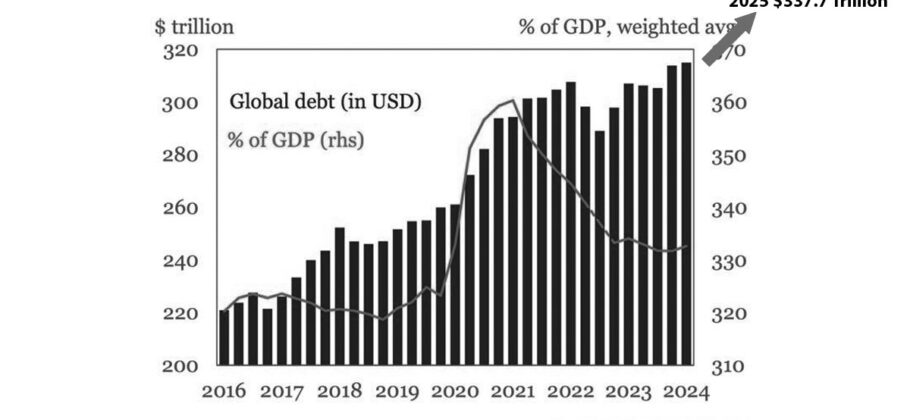

Global debt has climbed to an astonishing new record of 337.7 trillion dollars, according to the latest report from the Institute of International Finance (IIF). The increase of more than 21 trillion dollars in just six months marks one of the steepest surges in borrowing since the height of the pandemic. The report attributes the rise to easier global financial conditions, a weaker U.S. dollar, and a more accommodative stance from major central banks. This combination has encouraged both governments and corporations to take on new debt even as growth remains fragile.

The Breakdown of the Debt Surge

The IIF found that China, France, the United States, Germany, Britain, and Japan recorded the largest increases in debt levels in dollar terms. Part of this surge reflects the 9.75 percent drop in the value of the U.S. dollar since the start of the year, which made dollar-denominated borrowing appear cheaper for foreign borrowers. But currency effects only explain part of the picture. The real story is that much of the world remains addicted to low-cost debt and short-term fiscal stimulus.

The IIF report noted that the global debt-to-output ratio—an indicator of how much is owed compared to what is produced—remains above 324 percent. In emerging markets, the situation is even more concerning, with the ratio hitting 242.4 percent, the highest level ever recorded. Total debt in emerging economies grew by 3.4 trillion dollars in the second quarter alone, reaching over 109 trillion dollars.

According to Emre Tiftik, the IIF’s director of sustainability research, much of this expansion is linked to rising military expenditures and geopolitical instability. “Rising military spending will strain government balance sheets amid rising geopolitical tensions,” Tiftik warned. He explained that the increase in debt has been driven mainly by government borrowing, which has risen sharply across the G7 countries and China. “Bond market reactions have been harsher in advanced economies, with the yield on G7 10-year bonds near their highest since 2011,” he said.

A Surge Comparable to the Pandemic Era

The IIF emphasized that the current acceleration in debt levels mirrors the explosion seen in the second half of 2020, when governments worldwide borrowed aggressively to offset the impact of COVID-19. “The scale of this increase was comparable to the surge seen in H2 2020, when pandemic-related policy responses drove an unprecedented buildup in global debt,” the IIF stated. But unlike the pandemic era, the current increase has not been accompanied by a global emergency. Instead, it reflects a structural dependence on debt as the primary engine of economic growth.

In countries such as Canada, China, Saudi Arabia, and Poland, debt-to-GDP ratios rose sharply, signaling that borrowing continues to outpace economic output. Conversely, the ratios fell in Ireland, Japan, and Norway, though the declines were modest and insufficient to reverse the global trend.

Bond Market Stress and Fiscal Strains

The IIF cautioned that fiscal strains are likely to intensify in countries such as Japan, Germany, and France. It urged governments to be wary of “bond vigilantes,” the investors who sell off bonds from countries they believe have unsustainable debt. This phenomenon can drive up borrowing costs and create a feedback loop that worsens fiscal pressure.

“While government debt ratios rose sharply across emerging markets in H1 — most notably in Chile and China — market reaction has been stronger in mature markets this year,” the IIF noted. Emerging markets also face a daunting wall of repayments ahead, with nearly 3.2 trillion dollars in bonds and loans coming due in the remainder of 2025.

Japan’s situation stands out as particularly troubling. The nation already carries the highest debt burden in the developed world, equal to roughly 260 percent of its GDP. Long-term Japanese government bond yields have climbed to levels not seen since 1999. Economist William Pesek observed that the country’s predicament is a direct result of decades of ultra-loose monetary policy. “Each step the Bank of Japan takes to withdraw from the bond market, an army of debt traders push back,” Pesek wrote. The central bank’s governor, Kazuo Ueda, has effectively been forced to halt Tokyo’s tightening cycle because the cost of normalizing interest rates would likely trigger a financial shock.

Pesek likened Japan’s growth strategy to an athlete relying on performance enhancers. “Japan is an example of a developed economy that’s lost the plot of growing without stimulus. Think an athlete whose performance is only thanks to steroids and other short-term enhancers,” he said. “Eventually, those boosts lose potency and require bigger and bigger doses.” He added that China appears to be in a similar position, using fiscal and monetary injections to sustain a five percent growth rate that is becoming increasingly difficult to achieve without massive new borrowing.

The American Dilemma: Short-Term Borrowing and Long-Term Risk

The IIF’s report also raised alarms about the composition of U.S. government debt. Short-term borrowing now represents about 20 percent of total government debt and roughly 80 percent of all new Treasury issuance. This growing dependence on short-term paper could make the United States more vulnerable to interest rate shocks.

The IIF warned that this structure could “heighten political pressure on central banks to keep rates low, potentially threatening monetary policy independence.” In effect, governments may begin to lean on central banks to suppress borrowing costs, undermining their ability to fight inflation or stabilize currency values.

The U.S. national debt recently surpassed 37 trillion dollars, while interest payments are now among the largest single items in the federal budget. Even small increases in rates could ripple through the economy, raising mortgage costs, tightening credit, and increasing the risk of recession.

Why Global Debt Keeps Climbing

Analysts say the underlying cause of the debt explosion is a mix of political inertia, cheap money, and the belief that growth can always be borrowed. The post-pandemic era was supposed to mark a return to fiscal restraint, but instead, it ushered in another wave of borrowing fueled by populist spending programs, defense buildup, and industrial policy subsidies.

Governments continue to favor short-term stimulus over long-term reform, fearing that fiscal tightening could lead to political backlash or slower growth. Investors, meanwhile, are betting that central banks will intervene if conditions deteriorate, creating a moral hazard that encourages even more risk-taking.

As William Pesek put it, “Each time the system begins to tighten, policymakers step in with new support. It’s a cycle that gives central banks less and less latitude to raise rates.” That dynamic has left the global economy heavily dependent on low interest rates to sustain growth, even as inflationary pressures and geopolitical tensions increase.

A Precarious Future

The IIF’s warning is clear: the world’s debt is growing faster than its capacity to manage it. With trillions in repayments looming and interest rates still elevated, both developed and emerging economies are entering a phase of extreme vulnerability. Analysts are already speculating that nations such as the United Kingdom or France could face pressure to seek IMF assistance if borrowing costs continue to rise.

The IIF summed up the situation starkly, noting that the debt wave has left governments, corporations, and households alike with shrinking room to maneuver. The global financial system, it said, is now more interlinked and fragile than at any time since 2008.

At 338 trillion dollars, the world’s debt mountain represents more than three times the value of all goods and services produced each year. It is a mirror of global dependence on artificial growth and financial leverage. The question facing policymakers is no longer whether this burden can be sustained, but how long the illusion of stability can last before the next financial reckoning arrives.