Germany’s economic relationship with China is entering a new and far more hostile phase. While recent reporting by The Wall Street Journal helped surface how sharply attitudes have shifted inside German industry and government, what is now unfolding goes beyond any single article. Germany is openly questioning whether its largest trading partner has become a strategic threat rather than an asset. The language coming from Berlin increasingly resembles the language of separation. Not a clean break, but a deliberate and defensive divorce.

From Mutual Growth to Strategic Conflict

For years, Germany and China benefited from a simple arrangement. Germany supplied advanced machinery, chemicals, and vehicles. China bought those products, industrialized rapidly, and exported finished goods worldwide. The relationshi p helped fuel Germany’s export model and China’s rise as a manufacturing superpower.

That balance has collapsed. China now produces the same types of industrial equipment Germany once dominated, and often sells them faster and cheaper. German firms are no longer just losing ground in China. They are being undercut at home and across Europe by Chinese competitors that benefit from state subsidies, lower costs, and regulatory advantages.

As one analyst observed, China’s shift from buyer to producer of investment goods has been “meteoric.” Germany now finds itself competing against an industrial system it helped build.

Trade Statistics That Changed the Political Mood

The numbers behind Germany’s change in tone are stark.

German exports to China have fallen by roughly 25 percent since 2019. Imports from China have continued to rise sharply. Germany’s trade deficit in goods and services with China is expected to hit a record 88 billion euros this year, or about $102 billion, according to German government figures.

For the first time, Germany imports more capital goods from China than it exports there. In the second quarter of 2025, imports of manual gearboxes from China nearly tripled. German carmakers have seen their share of the Chinese market fall from about half to roughly one third in just two years.

Trade volumes remain enormous. Between January and September this year, total trade between Germany and China reached nearly 186 billion euros. That scale explains why Germany is not cutting ties outright, even as political pressure to reduce exposure grows.

Core Industries Under Direct Threat

The greatest pressure is hitting industries central to Germany’s economic identity.

Between 2019 and 2024, Germany lost its global market share lead to China in power generation equipment and machinery. Its advantage in chemicals and road vehicles has narrowed to the point of near parity. In electrical equipment, Germany now trails China by a wide margin.

The domestic impact has been severe. Germany’s manufacturing output is down 14 percent from its 2017 peak. The industrial sector has cut nearly 5 percent of its jobs since 2019. The auto sector alone has lost about 13 percent of its workforce.

In eastern Germany’s chemical belt, Chinese imports have surged. Chinese producers expanded their share of the European polyamide 6 market from 5 percent to 20 percent in a single year. Vedran Kujundzic of DOMO Chemicals said Chinese competitors typically offer prices about 20 percent lower.

“They are a constant presence,” Kujundzic said. “That pressure never stops.”

Christof Günther, who runs one of Germany’s largest chemical parks in Leuna, described a sector under strain. “Businesses can’t earn money,” he said. “They are cutting costs wherever possible, including jobs. They can only hold out for a certain time.”

Claims of Unfair Trade and State Backing

German industry groups increasingly argue that China’s rise comes from more than efficiency.

They cite low labor costs, a weak yuan, massive state subsidies, and regulatory barriers that disadvantage foreign firms. The Federation of German Industries labeled China a “systemic competitor” back in 2019. The VDMA machinery association has since accused China of unfair competition and called for antidumping measures and sanctions.

“We are free traders, but unfair trade policies cannot be tolerated any more,” said Oliver Richtberg, the VDMA’s head of foreign trade. “If China doesn’t play fair, we have to make them.”

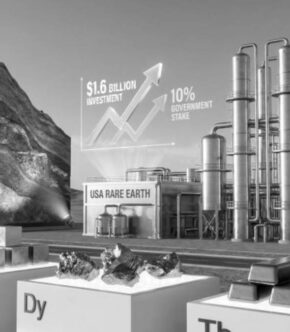

Another growing concern is China’s dominance of critical minerals. Germany’s National Security Council has discussed the risks of relying on China for rare earths, lithium, and other inputs essential for energy, defense, and advanced manufacturing.

What Germany Means by De-Risking

German officials stress that they are not seeking full separation from China. The term they use is de-risking.

De-risking means reducing dependence on a single country for strategically important goods, materials, and technologies. It involves diversifying supply chains, encouraging domestic and European production, and placing limits on Chinese access to sensitive sectors.

Several steps are already underway. Chancellor Friedrich Merz has promised protection for domestic steelmakers. His government has tightened bans on Chinese components in mobile data networks and supported buy European rules for public procurement.

Germany has also passed new laws giving authorities broad power to block Chinese technology from critical infrastructure, including energy, transport, health care, and digital systems. Merz has said plainly that Chinese components will not be allowed in Germany’s future 6G networks.

At the policy level, Berlin is preparing a new economic security strategy aimed at what one German official described as “the increasing economic, technological, and security risks” of dealing with China.

Despite the political shift, many German companies remain heavily invested in China.

China has once again overtaken the United States as Germany’s largest trading partner. German firms accounted for 57 percent of all EU foreign direct investment into China in the first half of 2024. That investment is still growing.

Major automakers continue to bet on China. BMW recently invested €3.8 billion in a battery project in Shenyang. A company spokesperson said China remains its largest single market and that there are no fundamental changes planned.

Rare earth traders also warn that alternatives are limited. Matthias Rüth, managing director of Tradium, said China still controls more than 95 percent of the rare earth market.

“You cannot replace this in a short time,” he said. “These are long standing and reliable trading relationships.”

Rüth added that recent disruptions stem largely from politics rather than suppliers. “The current difficulties come from political decisions,” he said.

The Shape of the Relationship Going Forward

Germany’s objective is not isolation but leverage.

Officials want better access to Chinese markets, fair competition, and guarantees that Chinese investment in Europe creates jobs and transfers know how. Analyst Noah Barkin said Europe is still open to Chinese investment, but only if Europe benefits.

“The question is whether China will agree to this,” Barkin said, “and if not, whether Europe is willing to close its market.”

Others warn Germany could retreat under pressure. Barkin cautioned against slipping back into what he called “Shanghai syndrome,” prioritizing short term gains if Berlin feels exposed to shifts in U.S. policy.

Conservative lawmaker Norbert Röttgen summarized the dilemma. “We need to reduce our dependence on China,” he said. “But if the U.S. lets us down, that will affect how we define our relationship with China.”

Germany’s message is now unmistakable. The era of blind faith in free trade with China is over. What replaces it will be a cautious, defensive relationship shaped by fear of losing the industrial foundation that made Germany prosperous in the first place.